The Emergent Writing Trajectory

One opportunity that geoblogging technologies offer a composition course is mapping as emergent writing. Through geoblogs, students and instructors not only research how technologies are shaped by everyday behaviors, but also apply technology as something other than an instrument. That is, geoblogs are not a way of getting “there.” They are multi-modal writing technologies, through which students and instructors may complicate the spatial logic of particular campus locations, not to mention the intended purposes of certain digital devices. A mobile phone may be compared with a pencil or a pen, or a blog may be more than a daily journal. In other words, the geoblog, as an emergent archive, lays bare both the device and the site of production, and with it collective mapping practices unfold.

For example, consider the Virtual University Geoblogging Project category, “The Quad.†At the University of Washington, the Quad is a highly trafficked zone, and, as you might notice, the captures categorized under “The Quad†suggest that the space serves various functions.

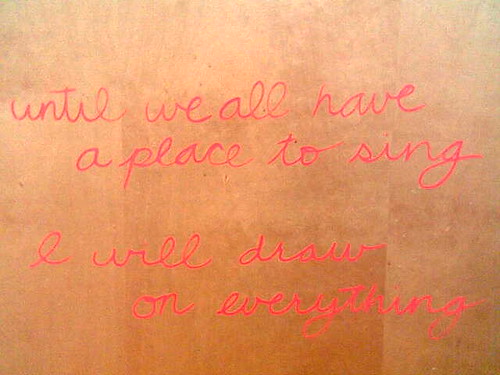

Some photos show student behaviors, while others focus on cherry blossoms and architecture. From some angles, the Quad is a place to stop, and from others it is a transit space. In a prompt such as Example Writing Prompt 2: “Capturing Evidence,” students might be asked to capture the Quad and analyze those captures as evidence to specifically define how the Quad functions. Here, both the capture and the analysis are forms of composition. According to Helen Liggett (1995), images (such as the ones above) might be considered interpretations of “spatial conventions” (p. 245), where space is “a generative component of social life” (p. 245). In terms of the geoblog, writing about evidence is not where composition begins. Instead, composition begins when students “compose” or “interpret” spatial conventions through their captures. It continues into the categorization and geolocation of those captures, into the assembly of them for the purposes of an argument, and of course, into the construction of arguments, a series of peer reviews, and reflections on writing choices. Rather than asking students to identify a form or theory by saying “that’s what I’m talking about,” geoblogging instead captures perspectives in order to see what forms emerge from them.

Of course, the trajectories of these mapping practices are not predictable. True, a geoblog might be databased and guided by protocols; nevertheless, as a collaborative technology, it also continuously compiles and connects in curious ways. One ongoing problem with the Internet is the question, “Where is it?†While the Geoblogging Project is searchable and tagged through various markers, the chances of getting lost are still quite numerous. However, we would like to think of exploring a virtual campus in a way that is similar to exploring an actual campus. Chance events occur. As students work together both in and out of the classroom, the geoblog encourages “encounter-possibilities” (Sirc, 2001, p. 15), which are time-stamped and located. Odds of students saying, “I was there, too†increase, and they can be asked to comment on individual entries that they recognize or write papers that articulate how composition and perspective intersect with the now historicized event. (For more, see Example Writing Prompt 4: “Re-Mapping.”) A place as large as the University of Washington campus is cut up and fragmented into smaller zones—Padelford Hall, Suzzallo Library, the Intramural Activities Building, and so on. Perhaps, then, through collaboration and collective evidence-gathering, sizeable research projects become less intimidating to students. Too, students can consider collaboration as a methodology. Much like writing that is repeatedly subjected to peer review, the geoblog is always in process.

Importantly, this model of emergent writing subverts the rhetorics of destination that are essential to the “built-environment” model of composition. In this virtual space, students don’t “arrive” at the correct model; they don’t find a perfect home in which to organize and simplify their observations. Instead, the compositions that emerge from encounters with the geoblog, like the encounters that compose it, can never be understood as “complete.” They facilitate a certain trajectory or intention and are composed in the explicit presence of numerous other possibilities. In fact, geoblogging allows instructors to preserve the “encounter” while giving students the agency to pursue their writing with a sense of context and purpose.

One such pursuit might begin with a prompt such as Example Writing Prompt 5: “This Map Matters.” In this prompt, students are asked to use the virtual university as a launching pad into composing a new campus map. As such, it asks students to make arguments (and things) that matter on their college campus. The map is not only a unique form of composition; it is also something that students, faculty, staff, and campus visitors can use. Thus the virtual university, as a class archive, becomes a space that is simultaneously grounded in geolocated actuality and rich with imaginative possibility. It gives students the opportunity to use the various skills, interests, and modes of thinking that they bring into a composition course in the service of actively producing something for a particular audience. Finally, given that the prompt relies heavily on a shared class archive, the virtual university provides students with the chance to compare and discuss their individual approaches to their new campus maps, how their perspectives on and strategies for the prompt differed, and how a variety of spatial interpretations and utilities emerged.

References:

Liggett, Helen. (1995). “City sights/sites of memories and dreams. In H. Liggett & D. C. Perry (Eds.), Spatial practices: Critical explorations in social/spatial theory (pp. 243-273).

Sirc, Geoffrey. (2001). Virtual urbanism. Computers and Composition, 18(1), 11-19.